If your child needs an operation, it will be performed at a hospital that has special expertise in heart surgery for children. This may be a hospital that’s familiar to you and your child, or it may be a different one with particular expertise in the operation that your child needs. It’s important for your child to be as healthy as possible for the operation. During the two weeks before the day of surgery it’s a good idea to keep your child away from people who have a cold or fever. If your child develops a fever, cough or cold during that time, talk to someone on the cardiology or surgical team to decide if the operation should be delayed.

Your child will be seen for preoperative counselling and testing the week before the scheduled surgery. At that visit it may be possible to arrange a tour of the hospital for you and your child. Common pre-operative tests include an electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, chest X-ray and blood testing.

Children are usually admitted to the hospital the morning of the operation or the day before. How long your child’s operation will take and how long your child will need to be in the hospital depend on your child’s heart condition and the operation that’s being done.

Sometimes the operating schedule has to be changed unexpectedly because of an emergency. You and your child should try to be prepared that emergencies with other children could delay or postpone your child’s operation.

It’s important to you prepare yourself, as well as your child, for the operation and hospital stay. Your child’s cardiac surgical team will give you information to help prepare for your child’s preoperative evaluation, surgery and hospitalization. Often there are nurses, child life specialists or social workers who are specially trained and available to answer your questions. Touring the hospital before the day of the operation may help you and your child better understand what the hospital stay will be like. To make your child more comfortable in the hospital, bring favourite toys, pictures, blankets, pillows or other belongings that remind your child of home. You may want to ask in advance about the hospital’s visiting times and policies about who can visit your child in the hospital. Often parents and guardians are allowed to stay overnight in the room with their child. If not, many hospitals have overnight accommodations for parents and guardians within the hospital or in the neighbourhood.

Blood transfusions are often needed for heart operations. The amount of blood required depends on the procedure. All blood donations are carefully screened to match your child’s blood type and to rule out infections, such as HIV/AIDS and hepatitis. Blood is sometimes in short supply, so it’s always appreciated when family members and friends give blood to the blood bank to replace the blood your child uses. It can be difficult to arrange to give your child the same blood you donated, but if you’d like more information about arranging donor-directed blood transfusions, contact your cardiac surgeon’s office.

Talking to your Child about their Surgery

What to tell your child about an operation depends on your child’s age, ability to understand and emotional maturity. Your pediatric cardiologist, cardiac surgeon and other specially trained medical and nursing staff at the hospital can help you decide how to explain the surgery to your child. It’s important to present simple, truthful information and answer any questions your child asks. If you don’t know the answer to a question, contact one of the specialists on your child’s team to help get the information.

Explain to your child should understand that there will be times when you will be separated during and after the operation. Reassure your child that you’ll never be far away and that you’ll return as soon as the doctors let you. Stress that this is a normal part of having surgery and not a form of punishment.

No matter how well you prepare your child for an operation, your child may sometimes be angry or depressed. At those times it may help to say that it’s perfectly normal to have these feelings, but try to remind your child why the surgery is important and needs to be done.

You can help your child by explaining why the surgery needs to be done in simple, clear words. Here are some approaches that parents have used to talk about surgery with their child:

“Your heart isn’t working as it should, but it can be fixed. The doctors and nurses are going to help your heart work better. I love you and I want this heart surgery done because it’s the only way for you to feel better.”

“During your operation the doctors will give you medicines so that you will be asleep and will not feel anything. After the surgery is over, you might feel sore, but your nurses will give you medicine to make your pain go away.”

“Right after the operation you’ll stay in a special room and get extra attention from the nurses and doctors. I’ll be able to stay with you very often and I’ll always be nearby. After you’ve gotten stronger, you’ll move to a regular hospital room. When you’re there, I will be able to stay with you almost all the time.”

“While you’re staying in the hospital, you’ll meet other children who are also getting well after their heart surgery. They’ll be getting ready to go home. You’ll be able to go home, too, as soon as the doctors say you’re ready.”

In the Operating Room

Heart operations in children are performed by a team that includes the cardiac surgeon, anesthesiologist, other physicians, percussionists, technicians, nurses, nurse practitioners and physician assistants. While the surgeon performs the operation the anesthesiologist gives your child anesthesia and monitors the vital signs.

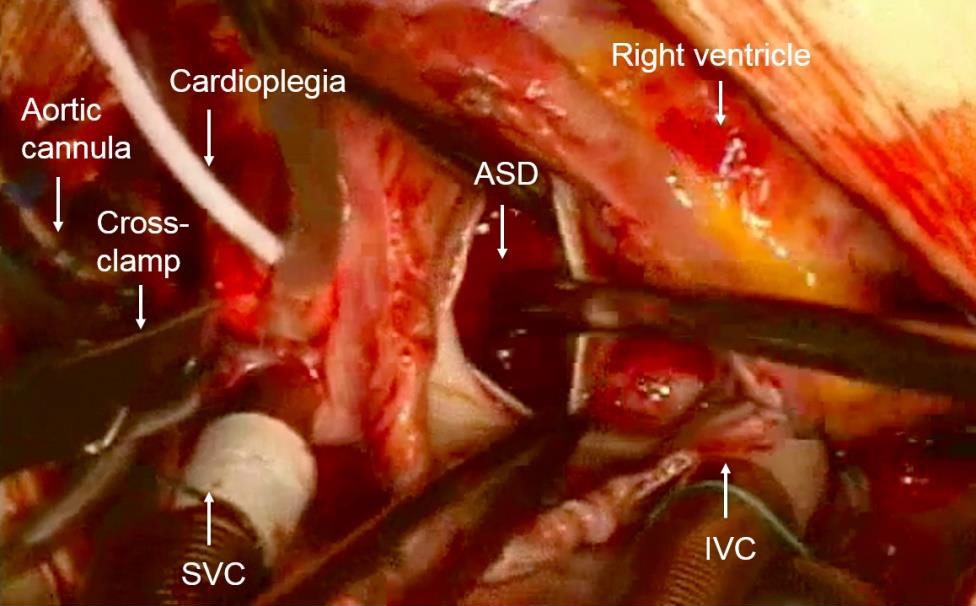

A heart-lung machine, which is also known as a cardiopulmonary bypass machine, is used during open-heart surgery. The heart-lung machine allows the blood to bypass the heart so the surgeon can empty the heart, opened and repaired it. The bypass machine removes the bluish blood before it enters the heart, pumps it through a machine that adds oxygen to it and makes it red again, and then pumps the red blood back into the body.

Once the heart-lung machine is working and the heart is emptied, the team will give your child a medication to stop the heart from pumping. The surgeon can then open the heart and do the operation. After the surgeon finishes the operation, he or she will close up the heart, allow the blood to fill it and start the heart’s pumping. Once the heart is pumping normally, the team will turn off and disconnect the heart lung machine.

Some operations on the blood vessels next to the heart don’t need the heart-lung machine. These types of operations are called closed-heart surgery.

In the Intensive Care Unit

After surgery your child will go to the intensive care unit (ICU). Specially trained doctors, nurses and technicians will give your child round-the-clock care.

Don’t be alarmed by all the equipment and tubes. Your child’s nurse or doctor will explain the purposes of the types of monitors, support and medications your child requires. Each of them is necessary to support your child and will be used only as long as needed.

The doctor may do blood tests, electrocardiograms, echocardiograms and chest X-rays to monitor your child’s heart function. Your child may also receive intravenous medications to increase blood pressure or heart rate or to allow the body to get rid of extra fluid that builds up during open-heart surgery. Your child will be kept as comfortable as possible with pain medications and sedatives.

Common types of monitoring and support used in the ICU include:

- Central venous line (CVL, CVP or right atrial line): A small tube, called a catheter, that’s used to give medications, fluids and to monitor the pressure in your child’s veins. The tube is placed directly into the heart through the chest wall or through one of the large veins in the body.

- Arterial line (Art line): A catheter that allows your child’s blood pressure to be measured continuously. The tube is commonly is placed into an artery in the wrist, groin or feet.

- Arterial Blood Gas (ABG): A test in which blood is drawn from the arterial line that gives information about how well the lungs and heart are working.

- Oxygen Saturation (Sat monitor): A small monitor attached to the finger or toe that allows the oxygen level in the artery to be monitored continuously.

- Mechanical ventilator (breathing machine): Many children need this to deliver oxygen to the lungs until they wake up from the operation and can breathe normally. The ventilator delivers oxygen to the lungs through a special tube called an endotracheal tube that’s placed down the throat into the windpipe.

- Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP): This special device is placed in your child’s nostrils to deliver oxygen under pressure. It can keep the lungs expanded without the use of a mechanical ventilator.

- Nasal Cannula: Small tubes placed into your child’s nostrils that deliver oxygen into the lungs.

- Chest tube: A tube that’s placed through small incisions in the chest wall into the space around the heart or the lungs to drain fluid and air produced by the operation. Your child may have one or more chest tubes. The doctor will remove the tubes once the air and fluid drainage goes away.

- Foley catheter: A tube that’s placed into the bladder to drain the urine continuously and make sure your child’s kidneys are working properly.

- Pacing wires: Small wires that are placed through the chest wall and attached directly to the heart. If your child has an abnormal rhythm, these wires can be used to restore the heart’s normal rhythm.

Further Hospital Care

After leaving the ICU, your child will go to a less intensive area of the hospital, often called “the floor” or “step-down unit.” In these areas, the medical team will monitor your child’s heart rate and rhythm using a continuous electrocardiogram system called telemetry. You’ll be able to play a bigger role in your child’s care and will most likely be able to stay overnight in the room with your child. The doctor will put your child on a program to encourage coughing and deep breathing, to help prevent lung collapse and infection. Encouraging your child to do normal activities, such as playing, walking and going to the bathroom, will speed your child’s recovery.

After surgery some children must eat a low-salt diet to reduce the build up of fluids in the body. The doctor may also prescribe medications such as diuretics, digoxin or antibiotics. You child may need to take these medications for some time after discharge from the hospital.

Some children may have a fever for the first few days after the operation. Fever can be a normal reaction to the surgery, but if the fever doesn’t go away, your doctors may run tests to find out the cause and how to treat it.

At first, your child may need pain medication, but pain often goes away within only a few days after the operation in most children.